harriet tubman’s lowcountry raid

Two days before the infamous “Burning of Bluffton”, in June of 1863, a Union gunboat raid on several nearby Combahee River rice plantations resulted in the escape and freedom of about 70 enslaved people. The raid would never have happened without the aid of local guide and scout, Harriet Tubman, who had information that would aid in navigation.

Young Harriet was serving with the Union on Hilton Head, where she was a valuable resource in scouting and providing underground information. It was decided that she should accompany the captain of the raid in order to point out the dangerous mines that were anchored at strategic spots on the Combahee. The barrier islands and complex tidal river system was a hazard to navigate for the Union warships. In addition, many shallow mines had been laid in some spots on the rivers.

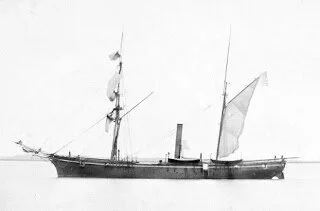

These vessels, referred to as “gunboats”, were wide-beamed, shallow-draft boats up to 180-ft. long, and were usually converted from merchant ships. See the Harper’s Weekly illustration of the raid, and note the size of these ships. They usually had one large-bore gun on the fore and aft. These guns were extremely heavy, and as result, the boats were cumbersome and tricky to steer.

As the side paddlewheel steamboats made their way up the river, where they trained their artillery on the plantation houses of the Heywards and other wealthy planters, many enslaved workers dove into the river and swam to the boats, where they were rescued and taken away. Over 70 enslaved rice workers found their freedom that day, and many later signed up to serve in the Union Army.

This was just one of many services that Harriet would provide to her fellow enslaved and to the Union forces throughout the war. Her influence was profound in our local history and her efforts to free and educate so many people are a part of our shared legacy.

HBF Completes Slave dwelling ProJeCt

The Historic Bluffton Foundation has completed the preservation of the slave dwelling located behind the Heyward House at 70 Boundary Street in historic downtown Bluffton.

The Heyward House’s slave dwelling stands as a powerful testament to our nation’s complex history, offering a tangible connection to the past and an opportunity for reflection and understanding.

Funding for the project was secured through the Town of Bluffton’s Preservation Grant and South Carolina Parks, Recreation & Tourism (SC PRT) funds and ATAX (Accommodation tax) funds. The Town of Bluffton’s grant generously contributed 75% of the funding, exemplifying their commitment to preserving our local heritage. An additional 25% of the funds was graciously provided through a SC PRT grant received this year.

Renovations included a preservation treatment on the shake roof to ensure its durability against the elements. There was one original shutter and the front door. The chosen color, haint blue, captures the essence of a shutter from an Edisto Island slave dwelling that was donated to the new African American History Museum in Washington, DC.

The Foundation credits Mr. David Pratt for much of the success of this achievement. Recognizing the value of the original flooring, Mr. Pratt executed sensitive and meticulous patch repairs, preserving as much of the original material and character as possible. The interior of the slave dwelling was painted with a traditional limewash treatment, using large bristle brushes to enrich its ambiance and preserve its historical essence. This work also led to an exciting discovery—an original corner pier—which provides clues about the building’s original position. Anecdotal historical information indicates that it was moved off its foundation during the 1893 hurricane and had new piers constructed during subsequent repairs.

The successful completion of this restoration project represents a significant milestone in our ongoing efforts to preserve and interpret our local history. The Heyward House Slave Dwelling will continue to serve as a timeless educational resource to gain a deeper appreciation for the experiences of those who were once enslaved.

BROTHER AGAINST BROTHER AT THE BATTLE OF PORT ROYAL

It all begins with an idea.

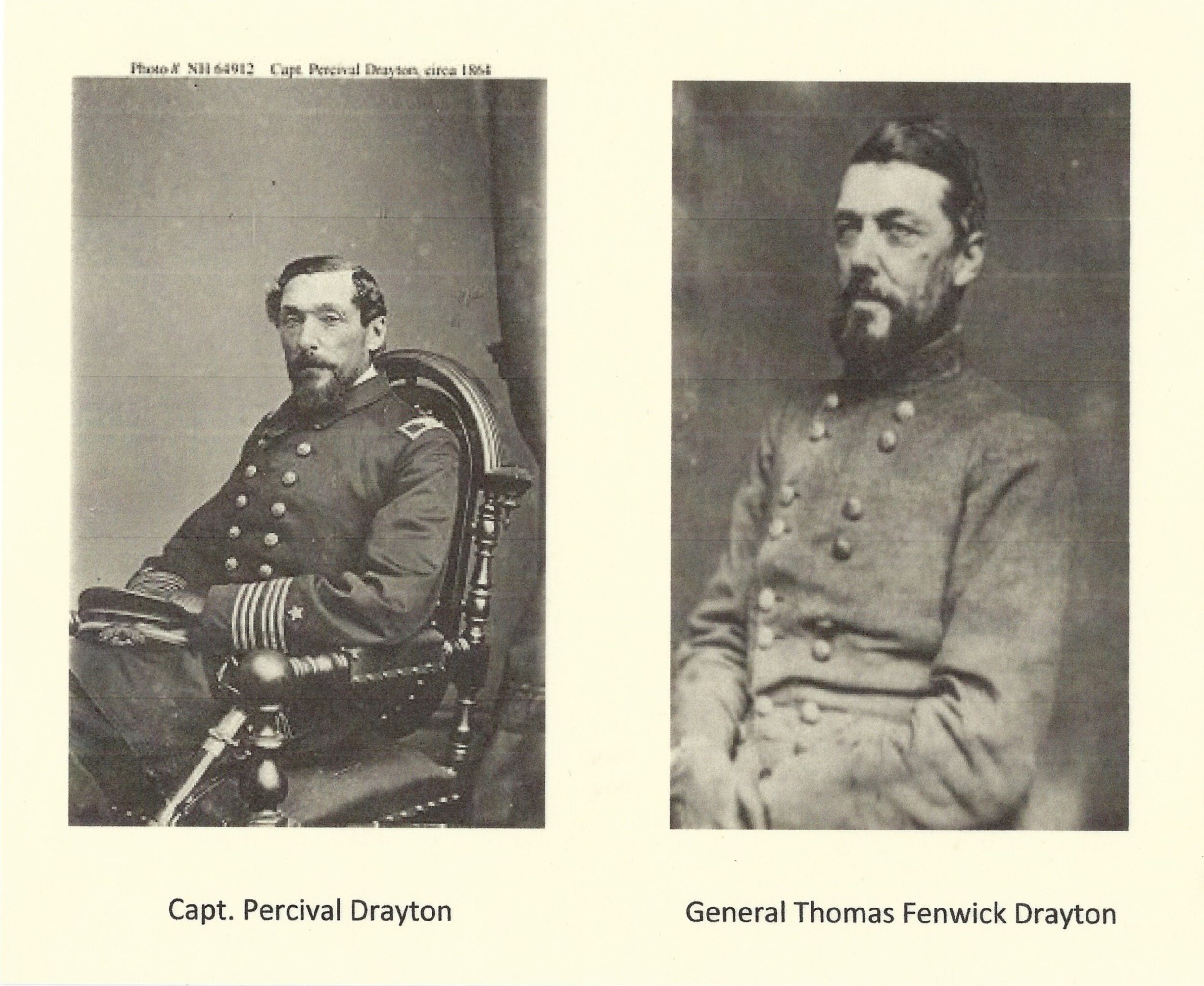

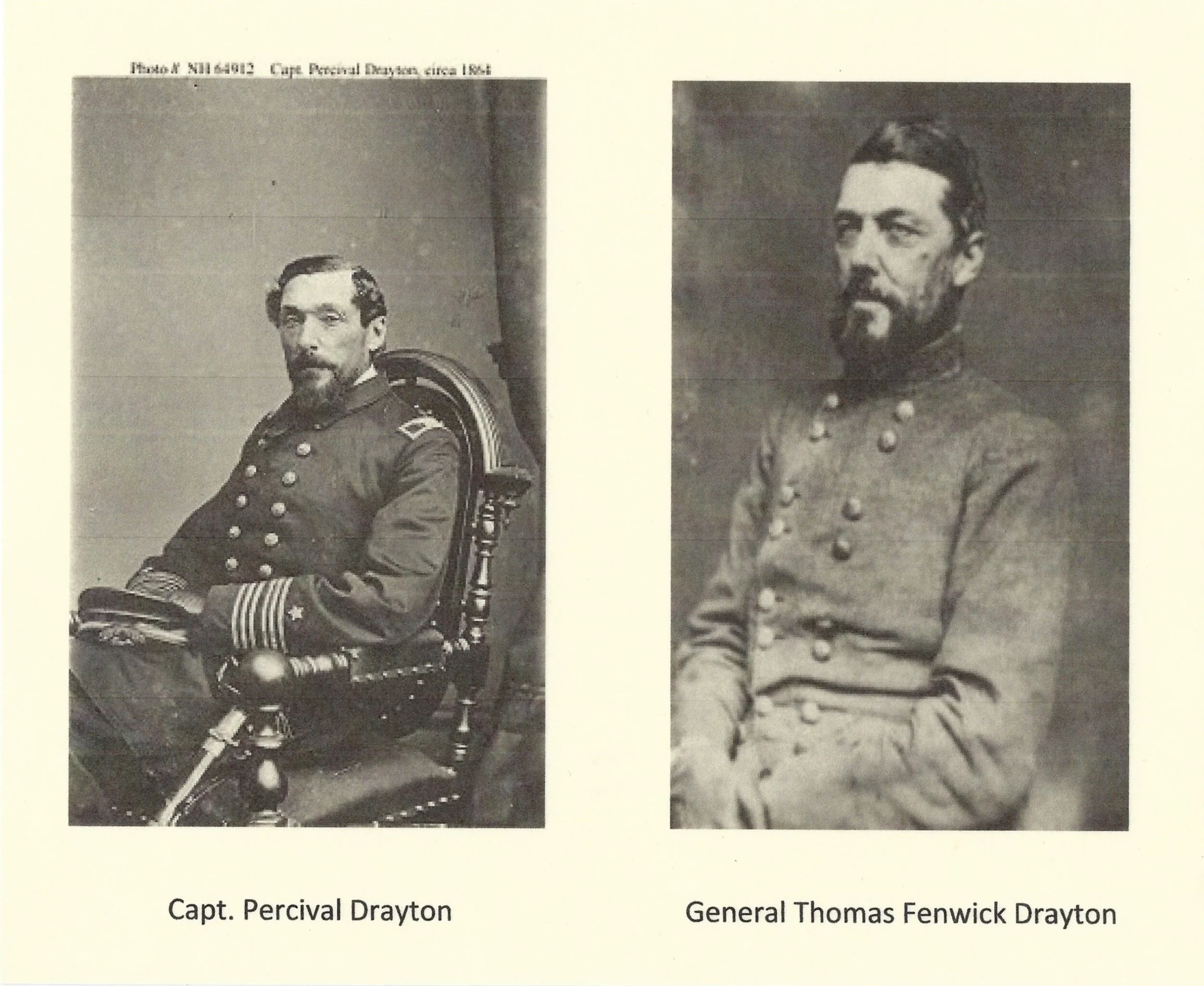

The first major naval battle of the Civil War happened in local waters, just months after the first shots of the war had been fired on Uniion-held Ft. Sumter, in Charleston harbor. The secretary of the navy had decided that the first major act of naval aggression against Confederate-held shipping lanes would occur in the strategic deep-water sound of Port Royal, between Hilton Head and present-day Hunting Island. Confederate forces held the defensive ramparts at Ft. Walker on Hilton Head, where General Thomas Drayton commanded about 1,000 troops, and occupied the fort's earthen works and mounted guns. Three miles across the sound, Ft. Beauregard's mounted guns presented a secondary target for the fleet that day, though none of Beauregard's defenses played a significant role in the battle.

Confederate General Thomas Drayton was a planter and statesman, who owned a large home in Bluffton, overlooking the May River from its position on the high bluff. Drayton married well, and his wife, Catherine Pope, brought Hilton Head Island's Fish Haul Plantation to his holidings, where he managed a large contingent of over one-hundred enslaved field workers and house servants. Thomas had trained at the United State Military College, where he was a classmate and friend of Jefferson Davis. Davis would later become the President of the Confederacy when war broke out in 1860. When the battle lines were drawn, Thomas chose to fight with his native state of South Carolina, while his brother Percival, who had moved north years before, chose the Union side, and became an officer in the US Navy. Fate would bring the Drayton brothers together on November 7, 1861, when the US Navy fleet sailed into Port Royal Sound with guns loaded, and with orders to take the rebel defense by force.

The flotilla of 77 US Navy ships that left for the planned trip south was the largest fleet of vessels to have ever sailed together under the US flag. Most of the ships had arrived in SC waters on November 3rd, 1861, after making their way through the storms and treacherous waters of NC's outer banks. Planned as a combined assault of naval bombardment with an infantry landing, the battle eventually became a purely naval artillery victory for the US forces. At the helm of the Union gunboat USS Pocahontas, Captain Percival Drayton was well aware that his brother, Thomas had been placed in command of the Confederate adversary at Fort Walker. The Union Navy's strategy was to enterthe Sound and form a "ring of fire," with the land-side ships firing broadside salvos into Fort Walker as they passed by. This newly-wrought battle tactic resulted in an almost non-stop deluge of exploding shells, which proved indefensible, decimating Fort Walker after a mere four hours of shelling. General Drayton and his men mostly escaped by retreating across the Calibougue Sound and tidal creeks to the mailand at Buckingham, with the aid of several large barges and under the cover of darkness. Loss of life had been suprisingly light, with only 250 rebel deaths throughout the battle, and only a few Union casualties. The quick retreat had saved many lives, though in their haste they left behind most of their belongings. Both Drayton brothers would eventually survive the battle, and the rest of the war as well. General Thomas Drayton later lost his home on Bluffton's May River when Union forces from Fort Pulaski burned most of Bluffton in June of 1863.

Newspapers of the day sent artists on location to battlefields, where they endeavored to create incredible etchings that captured the details of battle. Artists of the time made sketches and notes on the scene, transferring their visions onto steel plates when they returned to their studios in the city. These artworks would be printed, published and would become the main source for information and depection of the day's events.The newspapers made great fanfare of the large illustrations and maps that adorned their pages, bringing the details of war to the northern citizenry and the stories of battle to a shocked public. The Bluffton Historical Preservation Society, are proud owners, custodians and archivists for the Caldwell Archives, which house many of the photos, documents, maps and manuscripts for historic Bluffton. Today, these examples are rare indeed, and the images from the Caldwell Archives are testament to the trying timesthat made America what it is today; a country forged by valiant heroes, and tragic losses. One such amazing example is an article from the New York Herald, which is on loan to the archives, from the estate of a generous BHPS member and donor. In 1861, the Herald circulated 84,000 copies and called itself "the most largely circulated journal in the world." The newspapers's publisher stated that the function of the newspaper "is not to instruct but to startle and amuse." This rare article depicts the details of the actual battle of Port Royal, as represented to the nation in 1861. We are scanning and protecting the original document to ensure its safety and long life, but we also want to share these dramatic and rare portrayals of the tactics and the finer points of the battles that won our freedom.

Kelly Logan Graham is Executive Director of the Bluffton Historical Preservation Society, which owns and operates the Heyward House Museum, the official Welcome Center for the Town of Bluffton. Call 843-757-6293 or visit HeywardHouse.org

JOSEPH MELLICHAMP, BLUFFTON'S DEERTONGUE DOCTOR

It all begins with an idea.

Gillisonville, the frontier crossroads town in St. Luke's Parish, where Joseph Hinson Mellichamp was born in 1829, would become the Beaufort county seat in 1840. Twenty-five years later the town would be burned by General Sherman's troops, along with Beaufort county's records, which had been loaded onto wagons to take to Columbia. Luckily, the Mellichamps, had moved years before to James Island, near Charleston, where his father, Stiles Mellichamp, became minister and rector of Saint James church on James Island.

Mellichamp graduated from the college of South Carolina with a concentration in literature, and then graduated from the Medical College of South Carolina in Charleston in 1852. Upon graduation he came to Bluffton, where he was invited into practice with a young physician named James L. Pope. Mellichamp practiced with Dr. Pope for two years, before leaving for Europe to broaden his education and his horizons. He spent considerable time in England, Germany, Switzerland and six months in Dublin at Trinity College. Afterwards he spent a year in Paris, returning to Lowcountry in 1856, as a man of culture, on an English ship, as its physician.

Within a year or so after his return to Bluffton, Joseph married Sarah Elizabeth Pope, the sister of his business partner, James. When James became ill and died soon after, Mellichamp inherited his busy practice, tending to the medical needs of the wealthy planters and their dependents, which included the enslaved plantation work force. Dr. Mellichamp lived on Bridge Street, behind the Heyward House.

Though his skills as a doctor brought him success and notoriety, his true love was for plants. He spent countless hours foraging in the woods along the May River bluff for specimens and new discoveries. Mellichamp's tireless botanical studies of the insect-digesting Pitcher Plant, earned him the honor of having a variety of the species named for him. In a letter written to a friend, Mellichamp shows his articulate and passionate regard for nature and specifically for a local plant referred to as deertongue; "While returning from Savannah River alongside the sandy bluff I find Trilisa odoratissima, the deertongue, with its tall purple spikes, some of them deeply colored. I wondered at the great number of large and brilliant butterflies hovering over, and overhead the autumn sky all producing a sense of exhilaration and happiness".

Deertongue, as a plant was known, grew plentifully in the sandy soil around Bluffton, and Mellichamp gathered it on his long walks and dried it for sale to the perfume and the tobacco industries. Deertongue probably provided the first commercial industry in Bluffton, and there was a major buying center in nearby Statesboro, Georgia. The tobacco companies, in a practice that was not revealed until many years later, ground the dried plant and blended it with tobacco to produce an aromatic vanilla-like flavor. The practice was stopped in the 1970s, when it was discovered to have carcinogenic characteristics.

In 1895 Dr. Mellichamp was visited in Bluffton by the famous naturalist, John Muir, who spent an afternoon with Mellichamp talking in front of a blazing fire. Later, Mellichamp would visit the Muirs in California, where he experienced the "sequoia big trees" that he had always yearned to see.

As one of Mellichamp's colleagues eulogized after his death, "He was beloved by the poor people of the district who in a touching way mourned in the loss of their old doctor as his body was borne to the grave." A street in Bluffton is named after Mellichamp, and he is buried at the side of his wife, Sarah, at the St. Luke's churchyard in Pritchardville.

Kelly Logan Graham is the Executive Director of the Bluffton Historical Preservation Society, which owns and operates the Heyward House Museum, which is the official Welcome Center for the Town of Bluffton.

UNDER THIS BLUFFTON LIVE OAK EARLY SEEDS OF SECESSION WERE SOWN

It all begins with an idea.

Robert Barnwell Rhett was born in Beaufort, SC in 1800, and was admitted to the bar at the age of 21. When he was 25 years old he was elected to the SC state legislature, and is described as being full of "passion, excitement and fire; quick in movement and temper." He was a "crusader and revolutionist," who radically opposed the tariff on foreign products needed by the planters of the agricultural south.

In 1832 the federal tariff was increased, potentially crippling the southern economy, and a movement to nullify the tariff arose with Rhett at its center. A resulting compromise with President Andrew Jackson kept Rhett and the 'nullifiers' at bay until another increase of the tariff in 1842 brought animosity to the surface once again. The price of Carolina Gold rice had provided great wealth to the planters of South Carolina, and it was said that "her aristocracy reached its highest splendor", during these times. Pressure was on for the radicals like Rhett to rally the populace to resist the unfair tariffs, and he scheduled a series of political events across the state where his thoughts hinged on the radical notion of SC seceding from the Union in resistant rebellion. The first of these "fire-eater" events was held in Bluffton on July 31, 1844. The legacy of this mid-summer meeting has become an historic chapter in Bluffton's fascinating history.

Invitations were sent to area parishes, newspapers and "prominent" men in the Lowcountry. It had rained for three days before the scheduled event, and the hot July day may have had something to do with the special brand of fire and rhetoric that came from the quickly-constructed wooden platform. This invitation appeared in the Daily Georgian in Savannah:

"Dinner to the honorable R. B. Rhett. Those citizens of Bluffton and its vicinity who have untied in the tender of their hospitality to the Honorable R. B. Rhett respectfully invite all the citizens in Savannah to partake of their bounty and to hear his address this day the Thirty First."

At about 2:00 p.m., according to the Charleston Mercury, "carriages containing the ladies of Bluffton and many fair visitors," approached the May River banks where a great Live Oak tree had been chosen for the event's backdrop. To a large gathering, Rhett spoke for an hour and a half, interrupted only by cheers and applause. The Mercury account continues, "youth and old age of both sexes mingled together, hung breathless on every word, and the whole mass seemed as if moved by a single thought." Secession was a concept that was gathering momentum, and Bluffton was perceived as a 'hotbed' of radicalism.

After the dinner, newspaper accounts referred to the gathering as, "the Bluffton Movement", and local politicians of the day who supported Rhett became known as the "Bluffton Boys". William Calhoun, a colleague and popular SC politician, succeeded in quelling some of the momentum of Rhett's 'fire-eaters.' Though he agreed with many of Rhett's ideas, Calhoun felt that a strong radical and secessionist approach was wrong, and when a Bluffton candidate for governor was defeated by a Unionist, the movement lost much of its energy.

Sixteen years after the dinner under the 'Secession Oak', as it would become known, the flames of secession would again rise from the sparks of Rhett's ideas in South Carolina's legislature. The southern politics of rising taxes and tariffs would result in the state's secession from the Union on December 20, 1860. The first shots would follow at Charleston's Fort Sumter just four month's later, on April 12, 1861, as South Carolina plunged headlong into a ruinous Civil War.

Kelly Logan Graham is Executive Director of the Bluffton Historical Preservation Society, which owns and operates the Heyward House Museum, which is the official Welcome Center for the Town of Bluffton.

ROBERT SMALLS' LARGE LOWCOUNTRY LEGACY

It all begins with an idea.

Born in Beaufort to an enslaved mother and white father, Robert Smalls was only 23 years old when he created his daring plan to escape with his family from slavery to freedom. The War between the States was barely a year old, and South Carolina had been the first state to secede from the Union, as well as the first to fire shots of aggression in Charleston harbor at Fort Sumter. Union commanders had devised a plan to blockade the entire Southern seaboard, focusing on the critical shipping ports of Charleston and Savannah. Their "Anaconda Plan" involved stopping all sea-going freight, in order to strangle the lifeblood of the south's vital agricultural export trade of rice, cotton, and indigo with Europe.

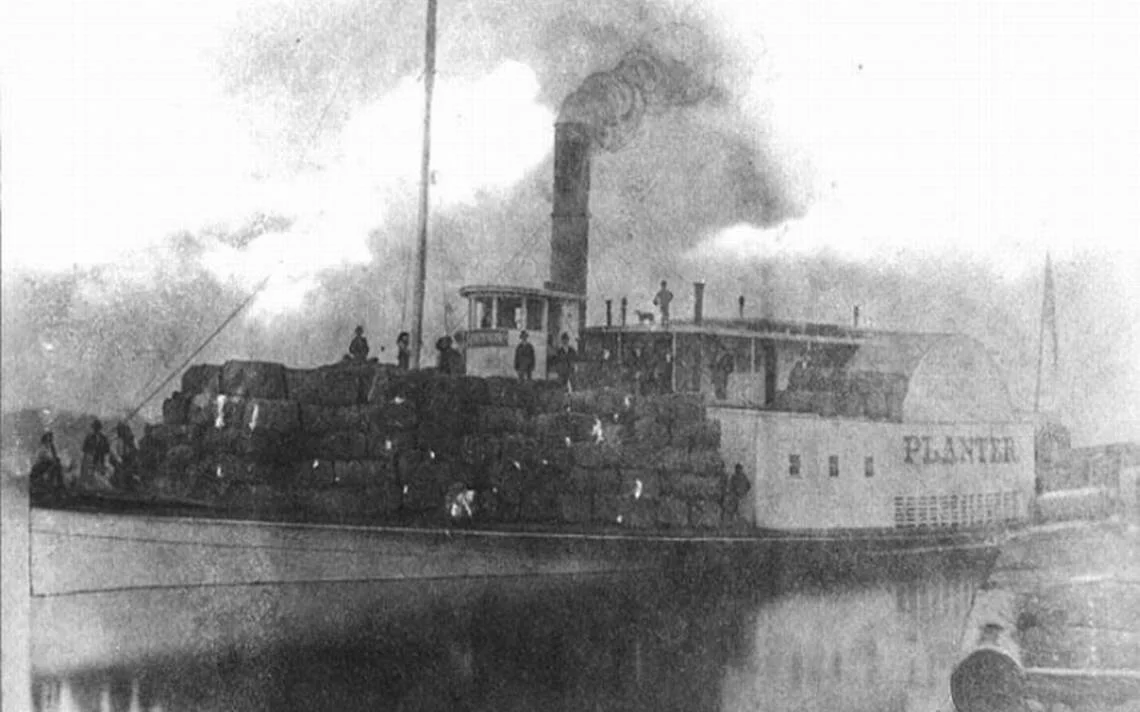

Because of the Union blockade, southern shipping was confined to the inner harbors and tidal rivers, where waterway ferry trade became critically important. Since he had grown up on the rivers of the Lowcountry, young Robert had become known as a skilled and trusted river pilot, and his services were hired for work in Charleston Harbor, ferrying troops and supplies for the Confederacy. Smalls had been assigned to work on the Planter, the most valuable vessel of military commerce in the Confederate-held harbor at the time. With a shallow-draft hull, the side-wheel steamer drew only five feet of water and her 140-length and 50-foot beam allowed the vessel to carry 1,400 bales of cotton at a time. At the time of the escape, the Planter was loaded with cannons and ammunition to be delivered to Fort Ripley, in the mouth of the harbor the very next day.

Smalls' plan was audacious; while the Confederate crew slept onshore, he lit the boiler fires and slipped away from the dock at 3:00 am, on the early morning of May 13, 1862. On board were his wife and three children, as well as eleven other men, women and children. The steamer's paddle wheels thrashed the salty water as the Planter pushed her way against the incoming tide toward the mouth of the harbor. As he passed the five armed Confederate sentries during their three-hour journey, Smalls imitated the physical stance and gestures of the Planter's absent Captain, down to the wide-brimmed straw hat that the captain was known to wear.

As the Planter approached the final sentry, Fort Sumter, in the early light of dawn, two long blasts and one short pull on the boat's steam whistles signaled their request to pass, which was met with an affirmative reply. Realizing too late that the Planter was heading out the harbor and toward the Union flotilla, the guns of the fort could not be trained and fired quickly enough to stop her escape. The Planter continued toward the Union blockade ship, Augusta, hoisting a huge white sheet as she approached. Smalls, his comrades, and their families were all subsequently granted their freedom and some were rewarded monetarily for their acts of bravery. The Harper's Weekly newspaper called the exploit, "one of the most daring and heroic adventures since the war commenced."

After the war, Smalls became a state representative from South Carolina and a five-term US Congressman, eventually returning to Beaufort to buy the house where he had grown up. Truly one of our treasured heroes for his brave and clever trickery, and the subsequent freedom of his compatriots, Robert Smalls represents one of our greatest Lowcountry stories. In the face of adversity, slavery, and persecution, Smalls led those 16 people into the promised land of freedom and into the hearts and pages of local lore.

Kelly Logan Graham is Executive Director of the Bluffton Historical Preservation Society, which owns and operates the Heyward House Museum, which is the official Welcome Center for the Town of Bluffton. Call 843-757-6293 or visit HeywardHouse.org

SOUTH CAROLINA'S 'BACK RIVER' OF RICE

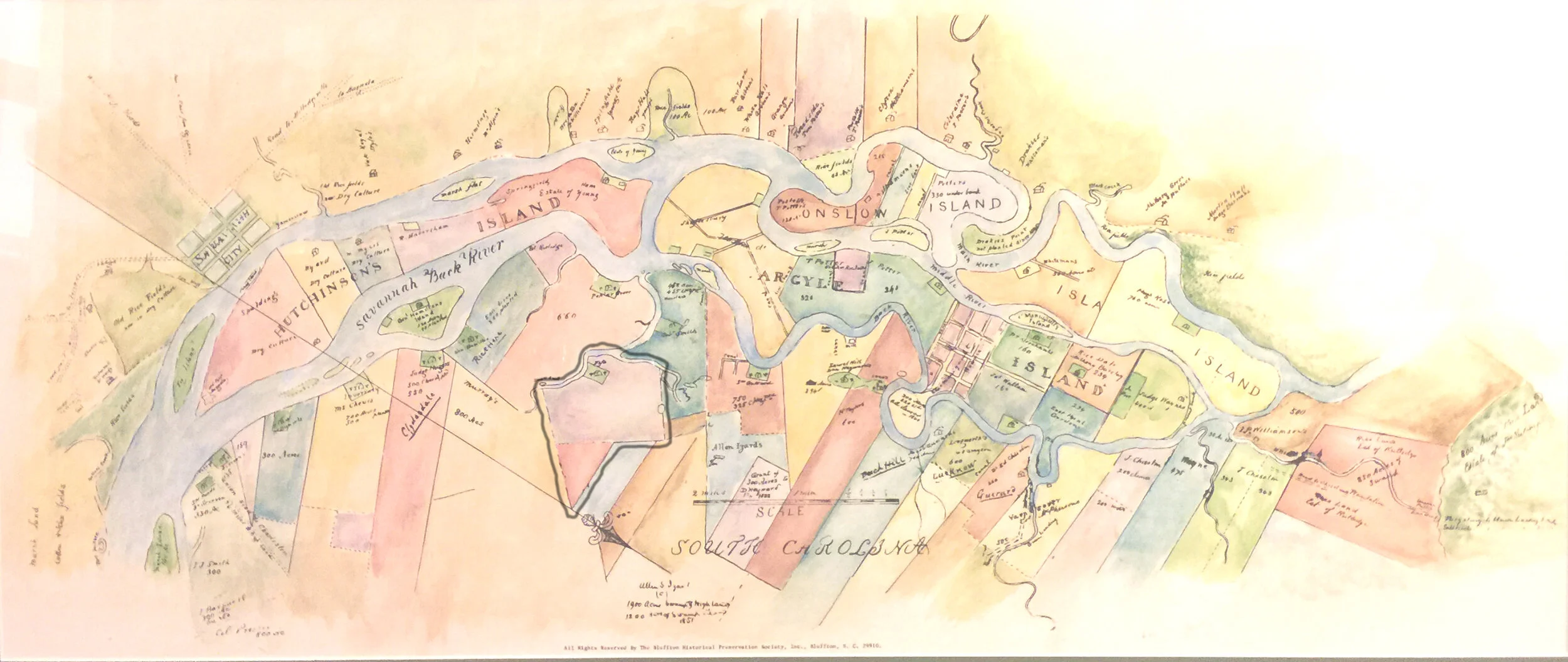

As you approach the Savannah River's Talmadge Bridge from the South Carolina side, the wide vistas of golden marshland that make up today's Savannah Wildlife Refuge seem as if they have always looked this way; but before the Civil War, these vistas contained more than 40 large rice plantations. The illustrated map from 1851 shows the carefully divided plantations, each owned by a wealthy southern planter, who visited only occasionally, leaving the overseeing to the appointed "drivers", who were trusted and rewarded for keeping the enslaved workforce on task. The great Savannah River that flows past the port city has two little sisters, the middle and back rivers, which fork and meander through the South Carolina marshes, creating a virtual shipping highway for the commerce of these perfectly positioned rice plantations.

One plantation that is shown on the map, is Fife Plantation, where Daniel Heyward inherited land and waterway access to the Savannah River. The "back river," wound its way along the South Carolina border, creating Hutchinson's, Onslow, Argyle and Isla Islands; all perfect for growing rice. Some of the richest and most powerful men are noted as owners on the many plantations drawn on the document. According to the original drawing, many of the planters "owned homes in Oakatee", (then a half of a day's ride away), where they would have spent most of their time. Many hands were required to work the rice fields, and 251 enslaved workers are listed in the hand-written list of names, sexes, ages and work assignments. Note the drivers, cooks, children's nurses, field workers and do. (domestic house workers), on the list, some noted as having been brought from Heyward's Combahee plantation, near present-day Okatee.

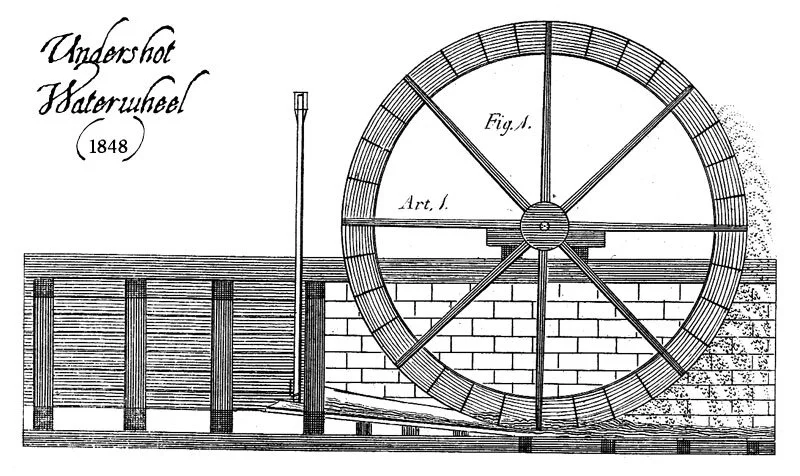

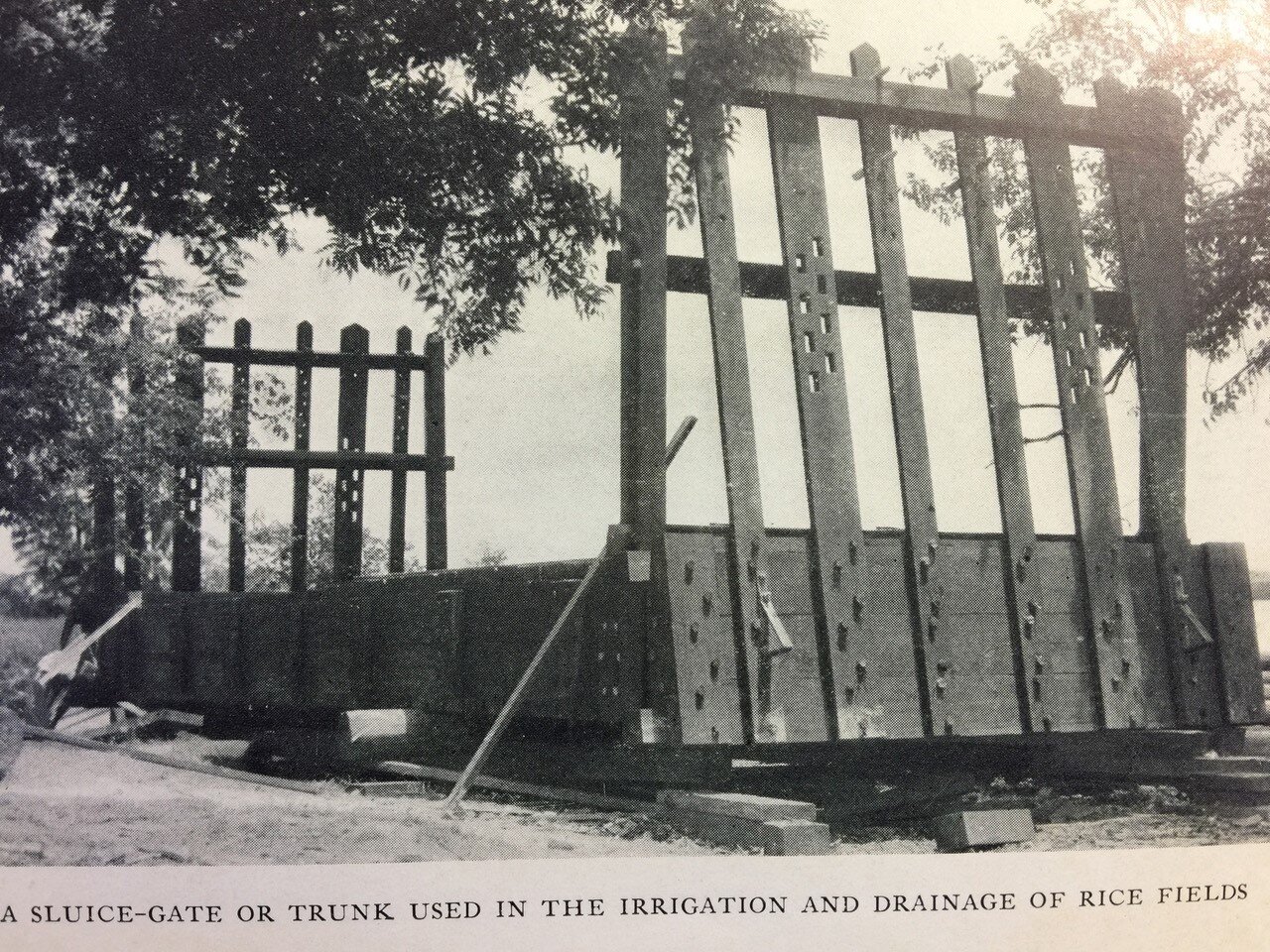

On the water's edge of each plantation, a green square indicates the location of the mill pond, where rice was gathered and milled for shipping. The location on the water provided more than the necessary transport by boat to market, it also provided the 'engine' that provided the power to mill the rice. An ingenious system that utilized hand-dug trenches, gates, and an undershot waterwheel, meant that during about four hours of the incoming tide, the power of the rushing water would spin the wheel. The gears and pulleys attached to the wheel transferred power indoors to the mill, where the rice was cracked and separated from the hull, before being bagged for shipment. During slack times when the tides were changing, the mill was silent, but when the tide changed and began to rush out, the gates were opened and the undershot wheel was back in action for another four hours of tidal action. Careful monitoring, and sometimes, 24-hour operation of the gates and mill made for demanding work.

The location of these particular plantations is vital to the hydro-engineering that made the Lowcountry marshes perfect for growing rice. These plantations, like the city of Savannah, are located over 8 miles inland from the ocean, where the strong currents of the Savannah River's fresh water can be utilized for the rice fields. The water in this section of the river stays fresh and is elevated and lowered with the tides because of the ocean's tides. The absolute genius is that these twice-daily tidal flushes of fresh water provided the pump as well as the incredible amount of water that was needed to grow and cultivate a rice crop.

The power of the rice dollar speaks to us through this map, where planters invested in the "Carolina Gold" rush that made Lowcountry rice the most sought after in the world for a time. Indeed, rice commanded a higher price on the European market than any other cargo except sugar. Carolina Gold made Charleston, SC the richest burgeoning city in the new world, where rice exports from the port made many men wealthy.

Today, as you drive toward the causeway and the Savannah bridge, imagine the spreading fields of rice, the humanity that would be seen in every field, toiling in the soggy marsh and fighting the sun and mosquitoes. With the end of the war, some freed people actually stayed on the failing ricelands, having nowhere else to go. All that now remains are a few crumbling structures, some old gates, and a few mill stones that are sinking slowly into the pluff mud, mill stones that once created the rice boom.

Kelly Logan Graham is Executive Director of the Bluffton Historical Preservation Society, which owns and operated the Heyward House Museum, which is the official Welcome Center for the Town of Bluffton. Call 843-757-6293 or visit HeywardHouse.org. BHPS owns the copyright for the SC Rice Plantation Map, reproductions are available, please contact us directly for information.

THE HEYWARD LEGACY IN BLUFFTON

George Cuthbert Heyward's horse arrived in Bluffton that evening without its mount. Retracing the path back toward the plantation where George had ridden earlier that day, with the cash payroll for his overseers and staff, they found his body beside the road and found that he had been shot. The immediate chaos that the incident threw the Heyward family into was devastating, and the older sons stepped in to help care for their mother and keep the home. The mystery surrounding his murder and the theft of the payroll would not be solved until many years later, when on his deathbed, a former subordinate in the military confessed to the crime, admitting his revenge taken after being passed over for a promotion in rank.

George Cuthbert Heyward's great-grandfather, Daniel Heyward, came from Charles Towne when he was awarded a land grant in Beaufort (then Granville) County. Starting with a 500-acre parcel in "Okeetee", he built a large plantation called Old House (and later Whitehall). With 7 enslaved West Africans, he raised rice and indigo, becoming one of the wealthiest and most successful planters in the area. His eldest son, Thomas, who has aspirations to control his future over the ever-escalating taxes and tariffs levied by the British, was compelled to enter politics and served as one of the earliest statesmen in South Carolina. Thomas went on to be one of the four signers of the Declaration of Independence from South Carolina.

In 1936, the Heyward of Old House welcomed a baby daughter, Anne, into the world. She would be the oldest of 4 children. Her youngest brother was Thomas Heyward, who many in Bluffton remember well to this day for his many contributions to our town, and after whom one of our downtown bridges is named. Anne tells the story of the pre-WWII days in Bluffton very well. "We moved to the Pine House on Heyward Cove in 1943, when Bridge Street was still oyster shell." She remembers the big storm when the "skid" foot-bridge across the cove blew down and was never replaced. Anne says, with a twinkling eye, "my daddy was the one who planted every palmetto tree along Calhoun Street." Anne's mother, Lucille, took the temporary title of "acting" Bluffton Postmaster in 1953 when the Postmaster (Ms. Harrison who lived at Seven Oaks) had a stroke and died suddenly. Lucille Heyward would hold that post for 22 years, until her retirement in 1975. Anne's father, Gaillard Stoney Heyward, served as the local state game warden from 1955-1965.

So what does, Anne, who is a willowy (and very active), senior, do for fun? She volunteers! She walks around Historic Bluffton sharing the stories of the homes and history of Bluffton. This amazing woman is an encyclopedia of Bluffton knowledge and her mind and memory are sharper than yours. She usually remembers the MONTH and the year that things happened years ago, and is glad to share her wealth of first-hand information. As she pauses in front of the Pine House, where she grew up as a little girl, one of many stories is told: "the little concrete bench near the cove is where I used to go when I was mad or upset; it became known as my 'pouting' bench." Her walking tours of Bluffton are told as only a gracious southern lady can tell them, with charm, culture and a keen dry wit.

Since that day 151 years ago, in 1867, when George Cuthbert Heyward was murdered, five generations of Heyward have lived in the house, until it was sold to the non-profit Bluffton Historical Preservation Society in 1998. Since then, the Heyward House has been lovingly maintained and operated as a house museum and since 2000 as the official Welcome Center for the town. The historic Heyward House is the familiar 'Blake House' yellow Carolina farmhouse with shuttered dormers and shiny tin roof in the heart of Bluffton's historic district where we tell the story of George Cuthbert Heyward, his family, and the succeeding generations of his family who held this house and its historical treasures for us to learn from and to enjoy. The Heyward legacy lives on and is well-represented by many like Anne Heyward.

Kelly Logan Graham is Executive Director of the Bluffton Historical Preservation Society, the non-profit group who own and operate the Heyward House Museum and Welcome Center. Call 843-757-6293 or visit HeywardHouse.org.

CAROLINA GOLD FROM WEST AFRICAN KNOWLEDGE

South Carolina has a history closely linked to agriculture and the bounty of our rich and fertile soil. Cotton and tobacco were always principal inland crops, but during the mid-1800s rice was king in the South Carolina Lowcountry. It is not clear when rice first came to the SC coast, but one story has a British merchant vessel in need of repair putting into Charleston harbor and paying for the work with a bag of Madagascar rice seed. Seeds need a skilled hand to grow, and no colonial southern planter had the knowledge or experience to grow rice.

So how and when did rice take hold in the fragile marshes of the Lowcountry? And how did rice become the second-highest yielding crop, (only to sugar), sold through the European trade routes? How did Charleston become the rice capital of the south - to this day consuming more per capita than any other city in America? The answers all come from Africa; West Africa to be precise.

For many centuries the people of the African Gold Coast, (present-day Ghana), Sierra Leone and the Ivory Coast have cultivated rice. Rice has long been a staple in their diet and they are well-known for their ingenuity in engineering and building canals to irrigate field crops. Even the sweetgrass baskets are descended from handmade winnowing baskets used to separate the rice husk from the grain.

These Africans also happened to be in the crosshairs of the burgeoning mid-Atlantic slave trade triangle between Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Many peaceful tribes of West Africans were enslaved and shipped to the new world by English, Portuguese and Dutch merchants who prospered mercilessly on their human cargos. When the abilities of these Africans to grow and cultivate rice became known in America, they brought premium prices as enslaved people. Charlestowne, as it was called at the time, (after King Charles of England), was a major point of disembarkation and sale in the booming slavery trade. After depositing their human cargo, the ships were filled with rice, cotton, indigo, and tobacco bound for lucrative European markets.

The flat, tidal Lowcountry marshes were well-suited to grow the golden grains that gave the rice its name, and that were so favored on the European plate. Rice is a very tedious crop to raise because it takes many hands to plant and most of the work is done in ankle, to knee-deep water. Fields must be drained and flooded four different times through the delicate growing cycle in order to yield a bountiful harvest. The dangers of snakes and malaria-carrying mosquitoes were always a risk to rice cultivation, and some field hands died as result of the harsh conditions in the hot summers, but west Africans proved more resilient to heat and disease than native American Indians.

Europeans developed quite a favorable taste for rice, and the supply could barely keep up with demand. Thomas Jefferson said that “Carolina Gold” was the finest rice that he had ever tasted, creating an endorsement that carried some weight in the marketplace. For a time in the mid-1800s, the Carolina Gold long-grain rice grown on southern plantations in the South Carolina Lowcountry commanded a higher price than most other export crops. During this productive time, the rice trade flourished and Charleston’s economy was larger than that of Philadelphia or New York.

South Carolina’s booming rice-driven economy was driven, not only by the muscle and sweat of the west African brow but by their knowledge and ingenuity to successfully grow and cultivate rice. When the war ended and the workforce was freed, rice came to a grinding halt as a “profitable” venture in the Lowcountry. Hundreds of acres of rice grew right here in Beaufort County at Garvey Hall Plantation. Some remaining canals are still in full view from highway 17 on the drive up the coast toward Charleston; deep and permanent scars in the heritage and culture of our collective and storied past.

Kelly Logan Graham is Executive Director of the Bluffton Historical Preservation Society, the non-profit group who own and operate the Heyward House Museum and Welcome Center. Call 843-757-6293 or visit HeywardHouse.org.

FREEDMAN, CYRUS GARVEY, BUILT HIS HOME ON THE MAY

In 1870, the Civil War had been over for several years, and most of Bluffton lay in ruin, having been burned and ransacked by Union troops seven years earlier. On the May Rivers high bluff, where a fine home had once stood, Cyrus Garvey obtained permission from his employer to build his own home.

Cyrus Garvey was an enterprising Lowcountry farmer, born into slavery in 1820, and raised on Garvey Hall Plantation, which is over 1,000 acres of land where the burgeoning Bluffton communities of New Riverside are now located. Cyrus’ mother was an enslaved plantation worker and his father was quite possibly plantation owner John Garvey, since Cyrus is listed as “mulatto” in the 1870 census. In that year, at the age of 41, Cyrus built his dream home on the bluff with his own hands.

After the war, Cyrus worked as a foreman for Joseph Baynard, who owned Montpelier Plantation, on the banks of the May River in present-day Palmetto Bluff. In fact, the location of the Cyrus Garvey House is directly across the river from where Montpelier Plantation’s fields once bordered the May, and it is not hard to imagine that Cyrus might have crossed the river by boat to work when the time and tide allowed. By the time the census was taken in 1870, Cyrus had already acquired 75 acres of land, a horse, a mule and four pigs. He married a woman named Ellie and they had a son named Isaac. Cyrus raised rice, cotton, Indian corn, peas, beans and sweet potatoes on his land, and he slaughtered and sold livestock as well. When the 15th amendment to the Constitution gave Freedmen the right to vote, Cyrus registered before the bill was yet ratified, becoming one of our state‘s first official African-American voters.

Garvey was indeed a good businessman, and he acquired an acre of land that would eventually become the site for St. Matthew’s Baptist Church in Pritchardville. On the deed of the land sale, in 1900, the illiterate man signs his name as Cyrus Garvey, once and for all establishing himself as a Garvey. The practice of taking the name of a former plantation owner was fairly common at the time, and it is evident that Cyrus had strong ties to Garvey Hall, and to John Garvey and his family name. Cyrus lived in the home that he built on the bluff for 20 years before buying the house and land from Baynard in 1890.

The very next year, in 1891, Cyrus purchased the land between his house and the river for $3.50. It is important to note that the land deed for this sale was signed by then SC Governor, Ben “Pitchfork” Tillman, who was an outspoken white supremacist. Reconstruction was not easy for a mulatto freedman, where many whites continued to shun African-Americans’ equality and rights. Only a clever and wise man could have navigated the social, racial and economic pressures of the times, and Cyrus was known to be a strongly spiritual man.

Today, Cyrus Garvin’s house still proudly stands on the high bluff overlooking the Bluffton Oyster Company and the May River below. Owned by Beaufort County, the house was lovingly rehabilitated by the Town of Bluffton and Beaufort County Land Trust with grants from public and private sources. Guided tours of the house with narrative about Cyrus Garvey are available, learn more by calling 843-757-6293

Kelly Logan Graham is Executive Director of the Bluffton Historical Preservation Society, which owns and operates the Heyward House Museum, which is the official Welcome Center for the Town of Bluffton.

THEY RETREATED TO BLUFFTON

When the first shots of the Civil War were fired at Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor, the move for South Carolina to secede from the Union had already been simmering for many years. As early as 1844, sixteen years before the start of the war, the seeds of discord were being sown by the SC “fire-eaters” who spoke loudly of secession from the United States. That early defeat at Fort Sumter, when confederates retook the harbor fort, had stung the Union badly, and a retaliatory move was soon made.

As part of President Lincoln’s plan to blockade and strangle the southern states, Union strategists chose a location to stage the first naval battle of the war where they could make a statement, and be assured of a victory by using their heavy naval guns. This location was to be Fort Walker on the north end of Hilton Head Island, on the strategically located Port Royal Sound. In a story of brother-against-brother, Fort Walker was commanded by General Thomas Drayton, whose brother, Captain Percival Drayton commanded the Pocahontas, one of the attacking Union ships. When the shells began to rain down from the “ring of fire”, a strategic circle of 25 gunboats, in the Port Royal Sound, the confederates soon realized that they could not hold the fort and fled for their lives. A group of five large boats moved confederate troops off of Hilton Head throughout the night, where they were brought ashore at Buckingham and retreated into and around Bluffton.

It was here in Bluffton, on the easily-defended 40-foot high bluff, that 300 confederate soldiers would remain, to spy, and fire small arms upon Union gunboats and steamers that came up the May and the Colleton Rivers. Just 17 months later, after many small skirmishes with the confederates in Bluffton, the commanding general at Savannah’s Fort Pulaski received orders to bring men and arms to burn Bluffton, in order to eradicate the troublesome rebels. On June 4th, 1863 several boatloads of Union soldiers moved into the Calibogue Sound and brought troops ashore to march west toward Bluffton. Gunboats, then proceeded up the May River and began shelling the town, sending the remaining townfolk scurrying for their lives. When the troops arrived on foot they proceeded with orders to burn the town, and two-thirds of the town’s homes and businesses were burned to the ground in a torch-fueled raid through historic Bluffton’s heart-pine buildings. Some of the homes that survived the fires were later robbed of their fine furnishings to be used in the officers’ quarters back at Fort Pulaski.

Today, The Heyward House is one of eight remaining houses that survived that hellish day in 1863. The reason that is was spared is unknown, but its value as a part of our past is clear. Built by the experienced hands of slaves in 1841, the Heyward House now serves as both a Museum and Welcome Center for the town of Bluffton. Tours of the house and walking tours of historic downtown Bluffton are offered daily to learn more about this area’s rich history and diverse culture.

Kelly Logan Graham is Executive Director of the Bluffton Historical Preservation Society, the non-profit group who own and operate the Heyward House Museum and Welcome Center. Call 843-757-6293 or contact us today!

THE HEART OF THE STORY

Listening to a good story is something we can all relate to. We remember stories and storytellers long after the end of the tale. Especially when the storyteller involves our imagination and relates on a level that makes the story real.

At the Heyward House, we are rich in stories, and in storytellers. The facts and legends that weave the thread of our historic social fabric is diverse and fascinating. The people that make our Museum and Welcome Center work are passionate about what they do. Telling others about the past involves an intimate working knowledge of people, places and dates that make the stories come to life. Listening to the 45-minute House Museum Tour, which is often delivered by a volunteer Docent, transports you to a time when life was simpler, and harder in many ways. Each Docent on our team has a unique and interesting style and perspective on their presentation. You can pick up different pieces of the historical puzzle each time you tour with a different Docent.

Come and hear the tales and wander back through time with tour guides who love what they do. You'll be transformed to a time when life along the May River was slow-paced and magical.